Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1032: 211-215, 2004

Lowering Cortisol and CVD Risk in Postmenopausal Women: A Pilot Study Using the Transcendental Meditation Program

Kenneth G. Walton, a,b Jeremy Z. Fields, b Debra K. Levitsky, b Dwight A. Harris, b Nirmal D. Pugh, c and Robert H. Schneider b

aInstitute for Natural Medicine and Prevention, College of Maharishi Consciousness-Based Health Care, Maharishi University of Management, Fairfield, IA 52557

cNational Center for Natural Products Research, School of Pharmacy, The University of Mississippi, University, MS 38677-1848

aCorresponding Author: Kenneth G. Walton, PhD

1000 N 4th Street, FM 1005, Fairfield, IA 52557

Phone: 641-472-4600 ext. 111

Fax: 641-472-4610

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is primarily a disease of the elderly. In the U.S., by age 65, CVD is the major cause of death in women as it is in men.1, 2 In women, the large increase in CVD risk that occurs during and after menopause is not entirely due to declines of sex hormones, because hormone replacement therapy does not remove CVD risk, in some cases only adding to it.3, 4

A more likely candidate for increased postmenopausal risk for CVD and CVD-related mortality is increased stress or increased stress responsiveness.5-10 Increased stress responsiveness after menopause has been observed in both cardiovascular and neuroendocrine systems.9, 11-13 Such stress-related alterations appear to be relevant to the observed differences in hemodynamics, left ventricular structure, and nighttime blood pressure dipping between pre- and postmenopausal women.14, 15 Evidence for a deleterious influence of menopause on fat metabolism also exists.16-18 Increased visceral fat is particularly strongly associated with chronic stress, with CVD, and with risk factors for CVD, including the cluster of risk factors identified as the “metabolic syndrome,”19, 20 including three or more of the following: hyperinsulinemia, hyperglycemia, abdominal obesity, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.

Excessive levels of the stress-induced hormone, cortisol, may play a role in this increased susceptibility to CVD in older women, and some natural medicine approaches may prevent or reverse this chronic increase of cortisol (see for review21). To explore the possibility that such approaches can reduce cortisol response to stress, we cross-sectionally examined the long-term effects of the Transcendental Meditation program, a component of the traditional system of health care known as Maharishi Consciousness-Based Health Care, previously reported to reduce stress, cortisol, and CVD risk.21

Methods

Data from 16 women (mean age = 75 y) who had practiced the Transcendental Meditation program long-term (mean = 23 y) were compared with data from 14 control women, matched for age, who had practiced no systematic program for stress reduction. For comparison, male subjects of the same age (10 Transcendental Meditation subjects and 11 controls) were also studied. Data on demographics, disease symptoms, and psychological variables were collected, and cortisol response to a metabolic stressor (75 g of glucose, administered orally) was examined in saliva and urine. Cortisol was analyzed by radioimmunoassay (Diagnostic Products Corporation, Los Angeles) as previously published,22 with a coefficient of variation of 3.6%. Other measures used standardized test instruments and procedures.

The testing procedure was as follows. Subjects began arriving at 10:30 hours and were asked to urinate in the toilet to empty their bladders. They recorded this time as the starting time for urine collections. Between this time and the end of testing (15:00 hours) all urine generated was collected in a single bottle for each subject, with the last timed urination occurring as close to 15:00 hours as possible. At 11:00 hours, all subjects began salivary collections and filled out questionnaires. Urine and saliva samples were stored frozen until assay. At 12:00 noon, subjects consumed 75 g of glucose in water flavored with the juice of lemon or lime. Blood pressure measurements were conducted throughout the period, with each subject being measured three times at least 15 minutes apart.

Results

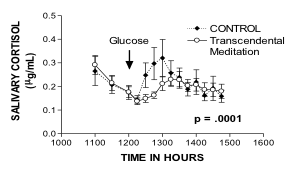

The control and Transcendental Meditation groups of women were not significantly different on demographic and life style variables (i.e. age, education, income, exercise level, smoking, alcohol consumption, and weight), nor were they different on family history of disease (i.e. CVD, cancer, and allergies). However, Figure 1 shows that the response of salivary cortisol to the glucose bolus administered at 12:00 hours was significantly different for the two groups of women (p = .0001, repeated measures ANOVA), with the control group rising 7.5 times faster than the Transcendental Meditation group between the 12:15 and 12:30 time points. In contrast, for the men, the control group responded only weakly to the glucose and was significantly less responsive than the Transcendental Meditation group (not shown). In the Transcendental Meditation subjects, the cortisol response to glucose was significant for the men’s and women’s groups and was of similar magnitude and duration in men and women.

Figure 1. Response of salivary cortisol to oral glucose in postmenopausal women. The statistical comparison is for those points after consumption of glucose, i.e. from 12:15 onward.

In women, the group differences in urinary excretion of cortisol over the 4-hour period were parallel to those in salivary cortisol. Control women were 3-fold greater in cortisol excretion than Transcendental Meditation women (2.4 ± 0.17 and 0.83 ± 0.10 µg/h, respectively; p = 2 x 10-4). The initial rate of glucose-induced rise in salivary cortisol, as shown by the difference between the 12:15 and 12:30 time points, correlated highly with urinary cortisol excretion across all women (Pearson correlation coefficient r = .82; n = 29, p < 5 x 10-4). On the other hand, cortisol excretion rates in men appeared not to correlate with the relative increases in salivary cortisol. Control men were 1.5-fold greater in urinary cortisol excretion than Transcendental Meditation men (1.89 ± .30 vs. 1.26 ± .14 µg/h, respectively; p = .06) despite the fact that salivary cortisol response to glucose was higher in the Transcendental Meditation men than in the control men.

Two other correlations were noteworthy. In the Transcendental Meditation group of women, number of months practicing the technique correlated negatively with cortisol excretion (r = -.63, p = .015). Number of months practicing the technique also correlated negatively with the number and severity of symptoms of heart disease, as determined by a nine-item questionnaire (r = -.91; p = 6 x 10-6).

Discussion

These findings suggest that long-term practice of the Transcendental Meditation program reduces the response of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis to a bolus of glucose in postmenopausal women. Studies in younger subjects, both men and women, also support a normalizing effect of this program on the HPA axis.22-24 The present findings are the first to suggest that a meditation technique can reduce effects of a metabolic stressor on the HPA axis. Because elevated cortisol may be a causal factor in producing metabolic syndrome, the apparent ability of the Transcendental Meditation program to reduce cortisol response to a metabolic stressor may play a role in the preventive effects of this program on CVD and coronary disease.25

References

- Wenger NK. Coronary heart disease: an older woman's major health risk. BMJ. 1997;315:1085-90.

- Lewis SJ. Cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal women: myths and reality. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:5E-10E.

- Welty FK. Women and cardiovascular risk. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:48J-52J.

- Nelson HD, LL Humphrey, P Nygren, SM Teutsch, JD Allan. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy: Scientific review. JAMA. 2002;288:872-881.

- Saab PG, KA Matthews, CM Stoney, RH McDonald. Premenopausal and postmenopausal women differ in their cardiovascular and neuroendocrine responses to behavioral stressors. Psychophysiology. 1989;26:270-280.

- Lindheim SR, RS Legro, L Bernstein, et al. Behavioral stress responses in premenopausal and postmenopausal women and the effects of estrogen. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:1831-1836.

- Owens JF, CM Stoney, KA Matthews. Menopausal status influences ambulatory blood pressure levels and blood pressure changes during mental stress. Circulation. 1993;88:2794-2802.

- Matthews KA, JF Owens, LH Kuller, K Sutton-Tyrrell, HC Lassila, SK Wolfson. Stress-induced pulse pressure change predicts women's carotid atherosclerosis. Stroke. 1998;29:1525-1530.

- Bairey Merz CN, W Kop, DS Krantz, KF Helmers, DS Berman, A Rozanski. Cardiovascular stress response and coronary artery disease: evidence of an adverse postmenopausal effect in women. Am Heart J. 1998;135:881-7.

- Chaput LA, SH Adams, JA Simon, et al. Hostility predicts recurrent events among postmenopausal women with coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:1092-9.

- Saab PG, KA Matthews, CM Stoney, RH McDonald. Premenopausal and postmenopausal women differ in their cardiovascular and neuroendocrine responses to behavioral stressors. Psychophysiology. 1989;26:270-80.

- Lindheim SR, RS Legro, L Bernstein, et al. Behavioral stress responses in premenopausal and postmenopausal women and the effects of estrogen. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:1831-6.

- Owens JF, CM Stoney, KA Matthews. Menopausal status influences ambulatory blood pressure levels and blood pressure changes during mental stress. Circulation. 1993;88:2794-802.

- Hinderliter AL, A Sherwood, JA Blumenthal, et al. Changes in hemodynamics and left ventricular structure after menopause. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:830-3.

- Sherwood A, R Thurston, P Steffen, JA Blumenthal, RA Waugh, AL Hinderliter. Blunted nighttime blood pressure dipping in postmenopausal women. Am J Hypertens. 2001;14:749-54.

- Torng PL, TC Su, FC Sung, et al. Effects of menopause on intraindividual changes in serum lipids, blood pressure, and body weight--the Chin-Shan Community Cardiovascular Cohort study. Atherosclerosis. 2002;161:409-15.

- Matthews KA, RR Wing, LH Kuller, EN Meilahn, P Plantinga. Influence of the perimenopause on cardiovascular risk factors and symptoms of middle-aged healthy women. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:2349-55.

- Lindquist P, C Bengtsson, L Lissner, C Bjorkelund. Cholesterol and triglyceride concentration as risk factors for myocardial infarction and death in women, with special reference to influence of age. J Intern Med. 2002;251:484-9.

- Hernandez-Ono A, G Monter-Carreola, J Zamora-Gonzalez, et al. Association of visceral fat with coronary risk factors in a population-based sample of postmenopausal women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:33-9.

- Van Pelt RE, EM Evans, KB Schechtman, AA Ehsani, WM Kohrt. Contributions of total and regional fat mass to risk for cardiovascular disease in older women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;282:E1023-8.

- Walton KG, RH Schneider, SI Nidich, JW Salerno, CK Nordstrom, CN Bairey-Merz. Psychosocial stress and cardiovascular disease 2: Effectiveness of the Transcendental Meditation program in treatment and prevention. Behavioral Medicine. 2002;28:106-123.

- Walton KG, N Pugh, P Gelderloos, P Macrae. Stress reduction and preventing hypertension: preliminary support for a psychoneuroendocrine mechanism. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 1995;1:263-283.

- Jevning R, AF Wilson, WR Smith. Adrenocortical activity during meditation. Hormones and Behavior. 1978;10:54-60.

- MacLean C, K Walton, S Wenneberg, et al. Effects of the Transcendental Meditation program on adaptive mechanisms: Changes in hormone levels and responses to stress after 4 months of practice. Psychoneuroendrocrinology. 1997;22:277-295.

- Puttonen S, L Keltikangas-Jarvinen, N Ravaja, J Viikari. Affects and autonomic cardiac reactivity during experimentally induced stress as relaeed to precursors of insulin resistance syndrome. Internat J Behav Med. 2003;10:106-124.